Newberry College and the story of James Lamar Cotton Spence

by Garry Spence - March 25, 2022

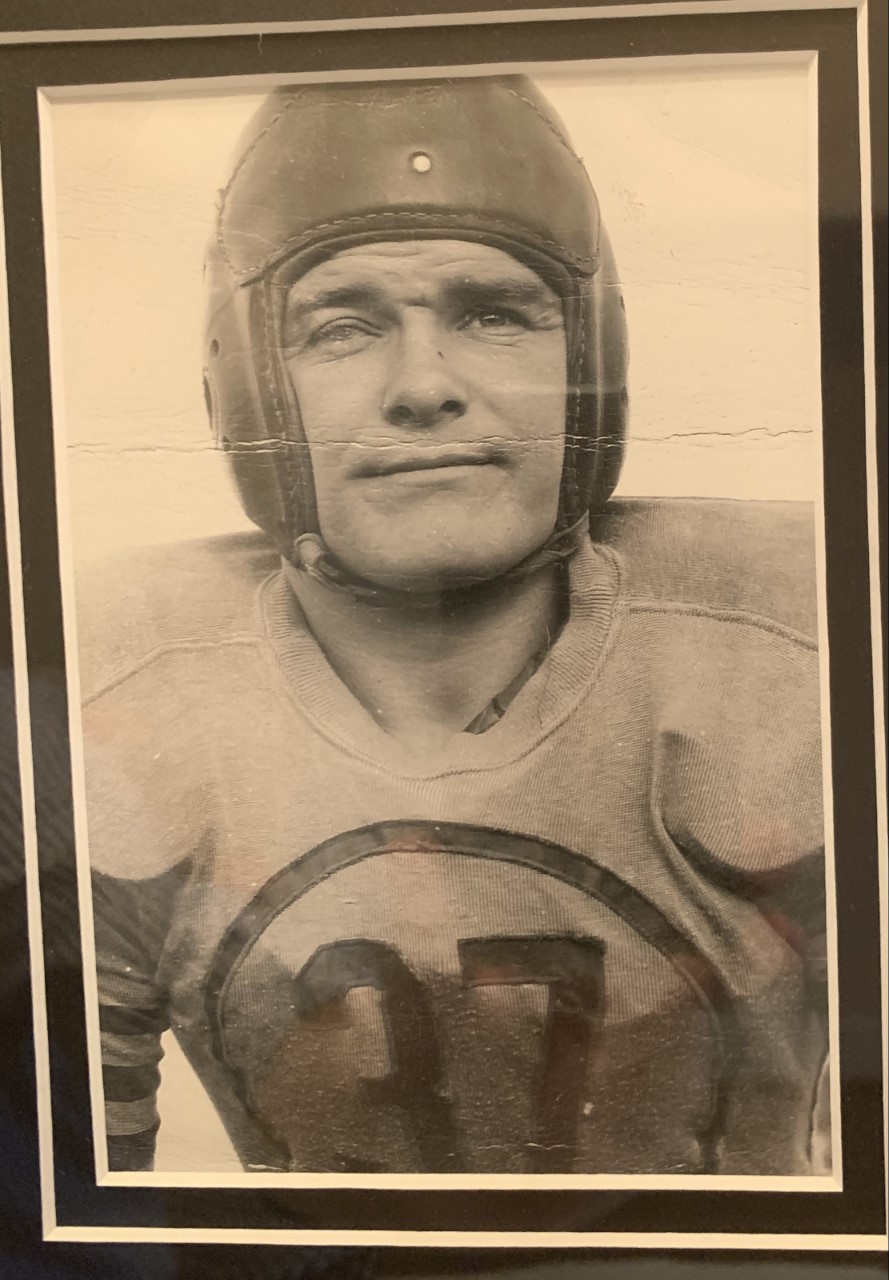

Lamar “Cotton” Spence is being honored in Newberry College’s new field house’s first floor, which will include the Lamar “Cotton” Spence Equipment Office.

The story of James Lamar Spence, or “Cotton,” as he was known on the Newberry College gridiron, is a lesson of triumph against overwhelming odds. Cotton played for Newberry 76 years ago, yet his journey serves as an inspiration to Newberry students and alumni today, and serves as a wonderful example of overcoming life’s challenges. Cotton’s composure and determination throughout adversity, demonstrates that you can take whatever hand you are dealt in life and excel.

Spence was an underdog who prevailed. He defied the odds, including physical disability, and massive personal setbacks, to become a standout football player at Newberry College in the 1940s. He was a quiet young man from humble beginnings who left his home in search of an opportunity. Along the way, this young man, though physically small in stature, left a giant impression on those he came in contact.

“Cotton” Spence was born and raised in the small textile mill town of LaGrange, Georgia. His father Matt was a supervisor in the mill and his mother Nancy a worked in the weave room.

At birth, Cotton was so small that his mother kept him in her bottom dresser drawer next to the bed rather than a crib. Afraid that he wouldn’t survive due to his premature size, she watched over him constantly.

Cotton was the oldest of three children, and several tragic incidents occurred which shaped his life forever, forcing him to grow up quickly. At the age of seven, Cotton lost his right eye in a classroom accident. He became totally blind in his right eye from that day on for the remainder of his life, often wearing a patch over his right eye to hide the damaged socket.

Three years later, tragedy struck again. Cotton lost his younger brother Jack to pneumonia, which was tremendously devasting to him. They were close pals and playmates, and Jack’s death had a profound effect on Cotton. Then, two years following Jack’s death, Cotton’s father became crippled and lost his job as overseer in the cotton mill. Times were hard during the Great depression, and at the age of 13 Cotton began digging ditches for Troup County to earn money to help support his mother and sister. These were tough but formative years where Cotton began to develop enormous physical strength and an enduring never quit attitude that would later serve him well on the Newberry gridiron.

When Cotton was freshman in high school, he was wrestling in gym class with a couple of boys. The high school football, Coach Oliver Hunnicutt, saw Cotton and admired his ability to wrestle older and larger upperclassmen. Hunnicutt asked, “Boy, what’s your name? Why don’t you come out for the football team?” Cotton replied, “Coach, you’ll have to ask my mother if I can play.” So, Coach Hunnicutt asked Cotton’s mother for permission, and she replied, “Absolutely not Oliver, he's too small to play football. And he only has one eye.” She was afraid that Cotton would get hurt and she couldn’t accept that fate, especially since she’d already lost one son to pneumonia. Coach Hunnicutt was persistent in his gruff but persuasive manner, and said that he needed someone with Cotton’s toughness and speed on his team. Nancy held firm and Cotton was not allowed to play football.

But Hunnicutt wouldn’t be denied and asked if Cotton could be the trainer or equipment manager for the team. He wanted him to be around the team. Reluctantly, Cotton’s mom agreed to allow him to help them prepare for the upcoming season. Within the first of week of practice Coach Hunnicutt began slipping Cotton into drills and scrimmages to see just how much this fast and strong player could help his team. Hunnicutt was so impressed with Cotton that despite not having permission from his mother, Hunnicutt had slated Cotton to be the starting offensive guard, starting defensive tackle, punter, and kicker for the high school team his sophomore year. Hunnicutt then went to Cotton’s mother before the first game and said “Nancy, this boy's got to play football. We need him.” Reluctantly she agreed, but she could never bring herself to go watch his football games for fear that he might get hurt. She never saw him play a single game.

Cotton went on to make All-NGIC for three consecutive years of Georgia high school football despite playing with only one eye. His handicap didn’t hold him back from excelling on the ball field. He was only five-foot-five and 155 -160 pounds his senior year, but he played like a 200 pounder. He played with such reckless abandon he was given about a half dozen nicknames by locals based on his playing style. He was called Mighty Little Lamar, Joe Buzzard, Wild Bill, Rabbit, and Cotton. Cotton came from his light-colored hair and his blazing speed like a “cotton tail rabbit”. He was known for his motor and his never quit attitude and according to one former teammate was considered pound for pound the hardest hitting football player to ever come out of LaGrange High school.

Because of Cotton’s high school football success and being voted Best Athlete at LaGrange High School, several college football programs showed interest in him. But college recruiting wasn’t a big thing in the 1940’s as it is today. There weren’t any films or photographs, only statistics from the games that were played and word of mouth from coaches and newspaper men. There were a few large schools such as Georgia Tech who admired Cotton’s football stats but upon learning of his small physical size for his position and having only one eye, they quickly passed on offering him an opportunity to play for their program. Also, WWII had just ended, and many big named players were returning from war to attend the larger Division 1 football programs.

But one of Cotton’s coaches had been writing back and forth with several colleges, including Furman. Furman had written a letter to the high school coach expressing an interest in Cotton coming up to play for them in the 1946 season. They had never seen him play, but his game statistics were impressive, and the letter said he would be a good fit for their football team. So, Cotton agreed to attend Furman in 1946 and play on the football team.

Money was scarce so Cotton’s family reached out to church members and neighbors in the Hillside community, and they raised enough money to buy a train ticket to South Carolina and $5.00 for living expenses. Cotton packed his duffel bag and set out for South Carolina. He didn't know exactly where he was going but knew he’d figure it out once he got there.

Well, somewhere along the way he either took the wrong train or got off at the wrong stop and he ended up near Newberry and not Furman. Not knowing exactly what town he was near, he asked the train porter if he knew where the college was located. He was told it was a few miles away and Cotton departed the train with his duffle and walked to the college. He arrived at the old field house, and met the Head football coach, Billy Laval. He said, “Hey, Coach, I'm Lamar Spence. I'm here to play football.” Coach Laval said, “You're who?” Cotton said, “I'm Lamar Spence from LaGrange, Georgia.” Coach Laval looked at this small kid and said, “Well, son, I don't have you on my roster. What position do you play?” “Offensive guard and defensive tackle,” replied Cotton.

Cotton then reached into his duffel bag and pulled out a letter, handed it to Coach Laval and said, “Here's a letter that says I can play.” The coach opened it up and he smiled and said, “Son, this is a letter to play at Furman. But if you’re good enough to play at Furman, you’re good enough to play at Newberry.”

Others on the coaching staff had concerns about Cotton’s size. All the other Newberry linemen averaged 6’ tall and 200lbs. The assistant coaches felt that he was a longshot to even make the team.

On the first day of practice Cotton goes to the equipment room to get fitted for his football equipment. He is assigned a helmet, shoulder pads, jersey, pants, and cleats. The equipment manager looked at Cotton’s small stature and asked, “What size cleats do you wear?” Cotton said size 8. The equipment manager said, “this is all we have,” and handed Cotton an old, worn-out pair of size 12 cleats. When Cotton put them on, the cleats were so big his feet came out of the shoes when he walked, even though tightly laced. But Cotton didn’t flinch.

Cotton took a roll of athletic tape and wrapped tape all around those size 12 cleats and his ankles. He even wrapped them halfway up his calf so that the cleats wouldn’t fall off. He then went out to the practice field on that first day and he did what he had always done throughout his lifetime. He played his game. He played full out. He was determined to show the coaches and especially the equipment manager how well he could play the game of football. Regardless of the cleats he was given, regardless of the naysayers, he took the cards he was dealt, and he played HIS game. He ran, blocked, tackled to the best of his abilities. and he put on a football clinic that day. He dominated!

The very next day, Cotton went to the equipment room to retrieve his clean uniform and football gear. He was looking for those dreaded size 12 cleats and a new roll of athletic tape when the equipment manager smiled from behind the counter and handed Cotton a brand-new pair of size 8 football cleats. He said, “Welcome to the team”.

Cotton took those size 8 cleats and used them to start at the offensive guard position on opening day of that season and every single game of his college career. He played so hard in those size 8 cleats that he became one of the top linemen in South Carolina during the 1946-47 collegiate football season. When the South Carolina All State honors were announced in 1947, Lamar “Cotton” Spence’s name was listed among them.

Cotton Spence had to return home to LaGrange after only two years at Newberry to support his family. Newberry taught him so much about life, about commitment, and teamwork. For the remainder of his life Cotton remained a passionate worker, a devoted husband, and a loving father of three. Cotton took pride in his work in textiles and worked in manufacturing until a plant closure forced him to retire “early” at the age of 81. He passed away June 27, 2013. He was known for his tremendous physical strength, a bone crushing handshake, and as being one of the kindest men on the planet.

One of Cotton’s children remarked that the equipment room was a fitting tribute to their father. “It’s a testament to his drive and determination to excel at what he loved and to overcome incredible odds. It was in the Newberry equipment room that Dad was initially challenged and had to prove himself. That single incident proved to be a defining moment in his football career at Newberry and ultimately in his life. Dad chose to accept that specific challenge head on and conquer it. Lamar “Cotton” Spence didn’t allow someone else to define his abilities or his desire. It is such a wonderful message of inspiration to students and underdogs everywhere. Never allow others to define you or your abilities.”

For more information about naming opportunities at Newberry College’s athletic stadium, please contact Bill Tiller, director of development for athletics, at 803.321.5676 or William.Tiller@newberry.edu.

Close

Close